Sweet Potentials

Uncertainty by degree

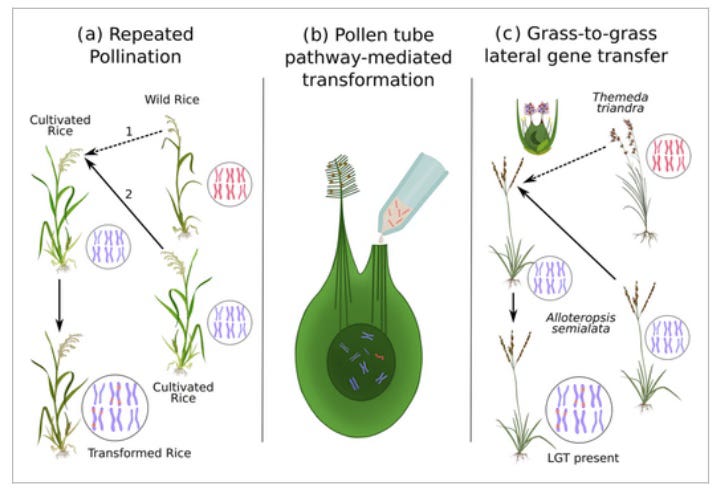

…much of the research reviewed here is beginning to show that the distinction between what we class as hybridization, transformation, and LGT [lateral gene transfer] may be less discrete than we first thought.

The mechanisms underpinning lateral gene transfer between grasses

Looking into studies on cross-pollination, there are a variety of interesting phenomena such as the mentor effect, xenia effect, pollen-induced genome shock, and lateral gene transfer. This essay discusses some of these phenomena in the context of a sweet potato experiment and plant breeding generally.

Sweet potato is an interesting crop. It is as a segmental allopolyploid, a thorough blend of three progenitor species with additional copies of chromosomes (source). Another fascinating aspect of the sweet potato is that it has acquired DNA laterally from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. This bacteria naturally occurs in soils, occasionally showing up as crown gall on plants. Plant scientists use this bacteria to facilitate genetic transformation or horizontal gene transfer. Therefore, the sweet potato is considered the first naturally transgenic crop (source). These aspects help explain why sweet potato seedlings are reported to have a higher plasticity than most crops, sometimes spontaneously changing phenotype.

This season was my second time sowing sweet potato seeds, which are not an easy thing to find. Although sweet potato is naturally a highly diverse crop, years of vegetative propagation have reduced its ability to make seed. Since a small number of independent plant breeders have been working to restore sweet potato’s ability to produce seed, this is starting to change. Seed that has already undergone selection for fertility is a head start allowing the latent diversity to be more easily unlocked. Last year, I grew just 10 seedlings. One had large white-fleshed tubers which never turn sweet despite long storage time. A lucky find, since was hoping for one that could be used in potato recipes.

The year I germinated and planted about 30 seedlings. For a few years I’ve been wanting to experiment with planting a single sweet potato seedling next to the wild relative species Ipomoea pandurata. The idea was to see how a fertile young I. batatas seedling would react to pollen from a distant wild species. There’s also an old Russian paper on Ipomoea distant hybridization that reported a low rate of seed set using I. pandurata pollen on sweet potato (source). My expectations were not high though, as Ipomoea is known to have fairly strong distant crossing barriers.

In sweet potato, interspecific hybridization takes place with varying degrees of success with closely related species in the Batatas section (source, source). One of the species sweet potato can cross relatively well with is the wild relative I. leucantha, which grows wild in the US and is weedy like many Ipomoea. Perhaps a self-sowing tetraploid sweet potato could be developed from this combination? Hybridizing sweet potato with a distantly related species like I. pandurata however is much more difficult. Some experimenters have made thousands of pollination attempts between distantly related Ipomoea species without success. In recent years however, researchers have made progress bypassing sweet potato’s distant crossing barriers using plant hormones. A mixture of GA3 and BA6 applied to the flower stalk for 10 days following pollination keeps the flowers from dropping and allows the hybrid embryos time to develop. Between 1/40 and 1/50 pollination attempts with this technique yields a distant interspecific sweet potato hybrid seedling (source). Five new interspecific sweet potato hybrids have been developed this way, each with a different distantly related pollen parent (hederacea, muricata, longcophylla, grandifolia, and purpurea). Surprisingly, these hybrids are very fertile (all but one are tetraploid). These studies reveals that the crossing barriers of sweet potato and its distant relatives exist primarily in the flower and early embryo development stage. The authors recommend new sweet potato interspecific hybrids be synthesized using this method. The full fertility of these tetraploids allows them be inter-crossed to develop complex multi-species sweet potato hybrids. Such crosses could thrive with lower effort in a wider array of ecosystems and conditions. Temperate perennials such as I. pandurata could offer winter freeze resistance to sweet potato tubers (hopefully without the disgusting glue).

One morning this summer (2025) a rabbit left a freshly pruned shoot of one of the sweet potato seedlings on the ground. I rooted it, took it to another garden, and placed the pot next to the wild I. pandurata vine. As the sweet potato started to flower, the pandurata vine was already huge with plenty of flowers. When virtually every flower on the sweet potato began to set seed, the seedling appeared to be self-pollinating. Although many sweet potato seedlings cannot, some self-pollinate very well. Interestingly however, when the pandurata vine stopped flowering in the beginning of September the sweet potato set no more seed, despite the 6 weeks or so of relatively warm weather that followed. It seemed like the I. pandurata pollen was physiologically active on the sweet potato flower. The simplest explanation is the distant “heterospecific” pollen caused the sweet potato to self-pollinate. In fact, polyploids like sweet potato are more likely than diploids to facultatively self-pollinate when exposed to heterospecific pollen (source). This pollen stimulation effect is called the “mentor pollen” effect. The term mentor pollination goes back to Ivan Michurin, who would apply a small amount of compatible pollen together with a more distant pollen to promote hybridization (he also used pollen mixes). The mentor pollen effect was later extended to include also instances where distant incompatible pollen induces self-pollination. Therefore, any pollen that acts to overcome incompatibility barriers can be referred to as mentor pollen, whether it’s a distant species, the same species, or a pollen mix. Considering that self- and cross-incompatibility barriers can have shared underlying mechanisms, the mentor pollen effect is an appropriate term whether applied to homospecfic pollen promoting outcrossing or heterospecific pollen causing self-pollination.

Upon harvesting the seed from the sweet potato exposed to pandurata pollen, it looked immediately distinct from the other sweet potato seed. The rest of the seeds, harvested in another garden with about 25 seedlings, were black (with a few brown ones). In a typical sweet potato, as the seed capsule matures and gets drier, the seeds go from brown to black. These mature seeds harvested near the I. pandurata however were light tan with dark spots, much lighter than even unripe brown seeds. Regardless of the stage of maturity or dryness of the seeds, they were clearly distinct and recognizable in a bag with the other sweet potato seeds. Having grown only a small number of sweet potato seedlings, I reached out to someone with more expertise, the person (Reed) who had originally developed this line of seedy sweet potatoes. He didn’t recall seeing any seeds like the tan spotted ones despite growing hundreds of seedlings over the years. This seems to suggest that the I. pandurata pollen was physiologically active down around the ovary of the sweet potato flower, altering the coloration of the seed coat. Although the seed coat is maternal tissue, heterospecific pollen can nonetheless affect its developmental expression. This phenomenon is called xenia when the pollen successfully fertilizes the emybryo. The related term metaxenia refers to heterospecific pollen altering maternal tissue while causing either self-pollination or clonal (nucellar) embryo formation.

Photo of the Ipomoea batatas seeds exposed to I. pandurata pollen:

When the seed capsule is brown but the pedicel is still green, the seeds are white with light spots. Once the flower pedicel is fully dry and the seed mature, the seed darkens and the spots become distinct. The not fully ripe white seeds were blown off by strong winds, but they still germinated.

Metaxenia/xenia effects originate at the interface where the pollen tubes meet the ovary. The combination of RNAs, hormones, and other biomolecules shed by the pollen can cause developmental shifts in the embryo even without fertilization. For the resultant seedlings, this stress can range from temporary epigenetic perturbation to a full genomic shock with transposon mobilization. In rice, intergeneric pollen has been used to select “mutator phenotypes” with a high degree of continuing variation.

When genetically analyzed, the seedlings were found to have close to 100% rice genome. In spite of the Zizania pollen not fertilizing the rice, a very small portion of its genetic material was able to transfer laterally into the rice embryo. The <.1% Zizania genes that transferred into the rice were found to be primarily transposons. Transposons are like the genomic version of weeds, during disturbances they come out of dormancy and spread. As they cut- and copy-paste themselves around, sometimes they make it into adjacent disturbed systems (horizontal transposon transfer).

“Overall, these experiments prove that the presence of heterospecific pollen from distant species during pollination can promote TE mobilization and transfer of genomic DNA from the donor species in the recipient genome. Although it is not clear where, when, and how the DNA exchanges happen, the presence of foreign pollen is enough to contaminate the reproductive process, without further human intervention.” (source)

Horizontal transfers to the embryo have even been made in several crops by simply dropping a solution of genes into a cut style hours after pollination (pollen tube pathway mediated transformation). In another set of experiments, the pollen itself is made a vehicle for genetic exchange (pollen tube mediated transformation).

Beyond the strange seed coat color, these 6 batatas seedlings seem to have a higher degree of general weirdness—two are low chlorophyll mutants, another appears to be polyembryonic (in this case two embryos in the same seed), and another is showing variegation in its first true leaf. I sent photos of them to a few true sweet potato seed growers. The only person who saw multi-stemmed seedlings (Reed) reported that he found them in the years his sweet potatoes grew next to a wild I. pandurata vine. Low chlorophyll mutants were estimated to occur less than 1% of the time. Based on these limited observations, the tan spotted sweet potato seed seem to contain embryos with a higher degree of plasticity than is typical. The application of foreign pollen to sweet potato, under certain conditions, appears to have potential as a selective force.

Photo: two partially fused seedlings from the same seed. Note the different stem colors.

Again, most likely the seeds were self-pollinated and gained a bit of plasticity from I. pandurata pollen signals. It’s also not out of the realm of possibility that some of the seedlings are true distant F1 hybrids, or even partial hybrids with small bits of laterally acquired genetic material. Regardless of the degree or nature of the variation of these seedlings, plant breeding experiments like these make us keep an open mind about possibilities and boundaries. Categories of selfing, crossing, lateral gene transfer, and vertical gene transfer are not always as rigidly distinct as we think. The sweet potato itself is already an example of blurred categories—bacteria/plant, natural/genetically engineered. In fact, the laterally transferred agrobacerium genes aren’t simply dormant traces of an ancient event, they are actively expressed in the sweet potato (source).

“the [sweet potato] plant can produce agrocinopine, a sugar-phosphodiester opine considered to be utilized by some strains of Agrobacterium spp. in crown gall”

Sweet potato produces agrocinopine just like an actual plant gal. In a real sense, the sweet potato is part cultivated gall. Agrocinopine allows agrobacterium to utilize the plant for energy.

These sweet potato seedlings provide an excellent opportunity to test the idea that plasticity can be amplified across generations by repeating the stress. Off-type seedlings are selected, exposed to heterospecific pollen, the seed harvested, and repeat. Like the successive grafting experiments, this could have a snowball effect that intensifies seedling plasticity. Successive heterospecific pollen exposure might also be able to condition and select the batatas seedlings for more complete cross-fertilization between the two species.

Ecology has two main branches, the study of individual organisms (autecology) and the study of ecological networks (synecology). The uniqueness of ecology that separates it from biology comes from community ecology (synecology). Therefore, an ecological view of heredity and plant breeding is likewise process-oriented. Rather than just steering allele frequency, its about managing feedback systems of stress, exchange, and plasticity. In addition to the bottom-up selective pressure of individual genes and organisms, community ecology reveals that network feedbacks are a top-down selective force. The units of selection become dynamic networks.

Amazing article, thank you. I did not know about the xenia expression in the seed coat. I can't say I've seen spotted light brown sweet potato seeds in my mix yet, but I do keep have Ipomoea pandurata growing so crossing is a possibility. This year, I had a variegated sweet potato seedling. It did not thrive, and remained a tiny plant all season barely putting on vegetative growth and no tubers. I also had general seedling weirdness, for example, a few seedlings with three cotyledon leaves rather than two. At least one seedling with a single cotyledon. I have assumed these effects are due to general genetic weirdness within sweet potato as it stands, but it's intriguing to wonder about potential pollen effects from the pandurata. I'll have to make some controlled crosses next year. And, I'll be sharing about my true sweet potato seed growing soon before this year is out (I grew over 120 seedlings this season).

So many gems in this article. I love the concept of repeated generations of foreign pollen exposure making pollination barriers more gentle for future hybridization. Reading your work reveals to me just how many fascinating scientific experiments have already been done in the realm of strange botany, and at the same time, all the uncharted potential. For me, nothing is more exciting. There are unimaginable botanical futures lying dormant, just waiting to be born.