Sweet Potentials pt. 2

A distant hybrid family

The first seedling to flower, the anthers had reduced production of clumpy pollen.

At the end of the first essay on the sweet potato heterospecific pollen experiment, it started to become clear that the seedlings were going through genome shock. As they have continued to grow, they seem more and more to be a big F1 hybrid family. Here are some observations and tentative conclusions about them up to this point.

Currently the seedlings are vining out and setting many flower buds. This twining growth habit is itself an interesting thing. Typically the climbing or twining trait is relatively uncommon in sweet potatoes, which have been mostly selected for bushy or trailing growth. Trailing refers to the cascading habit that you see often in ornamental potted sweet potato cultivars. Twining refers to long climbing stems that want to go upward and wrap themselves around something. In Sweet Potentials pt. 1, I mention that a rabbit pruned a sweet potato seedling that was twining up a chicken wire enclosure. I decided to root that cutting and use it as the seed parent for the cross. There was a selection process at play there, because only one seedling in that patch of ~25 had the ability to go vertical and twine around the chicken wire. That seedling had thin, hairy, twining stems. This is a more wild phenotype that sometimes show up in sweet potato seedlings. It is considered to be an ancestral throwback to I. trifida, one of the species that makes up the sweet potato genome. Climbing is also the general growth habit in the Convulvulaceae family. During the domestication process of sweet potato, the climbing habit was selected against, shortening the vines so they can put more energy into root production. The sunnier, less competitive context of the cultivated field also made climbing much less necessary. Through domestication the sweet potato stems also got thicker and lost their hair (“pubescent to glabrous”).

With the unexpected success of this distant hybridization experiment, I have to wonder whether the wild-looking seed parent was part of the reason behind it. It could be the case that domestic phenotypes have increased the crossing barriers in the flower, which can happen during a long-term domestication process. It must also have something to do with the general fertility of the sweet potato seedlings that were used, having already been selected over years to produce many flowers and seeds. This is a significant difference in experimental conditions compared to every published scientific study on sweet potato wide hybridization, which exclusively used vegetatively propagated I. batatas accessions. Typical sweet potato cultivars have highly reduced seed set and sterile pollen, diminishing the potential for both homospecific and heterospecific crosses. The idea in setting up this experiment was to test this hypothesis — would a young seedling be more open to distantly-related heterospecific pollen? Even after only a couple years of cloning, sweet potato seed production is known to be lower than its first season from germination.

Reading the other essays here, the influence of Ivan Michurin’s principles and methods of plant breeding is clear. One of Michurin’s tips to increase the odds of distant hybridization is to use a seed parent (particularly a hybrid) in its very first flowering. I had this in mind with this experiment, also because sweet potato is a highly heterozygous 3-species hybrid. Additionally, the fact that sweet potato has very little chromosomal barriers to distant hybridization makes it very promising to generate new multi-species swarms. The wide crossing barriers in sweet potato are fairly strong, but they mostly happen in the flower (source).

Another tip from Michurin is to never let hybrid seed dry out. Wide hybrid seeds can contain much more fragile embryos than a normal seed. Even a little bit of dryness can greatly reduce the seed viability. Hybrid seed must be immediately placed in moist media for germination or cold stratification. This is why my sweet potato seedlings are growing currently under lights in winter.

One aspect of wide hybrids that Michurin discusses extensively is their plasticity. The sweet potato hybrid seedlings have unsurprisingly shown a significant degree of plasticity. At first, the behavior of the seedlings was very confused and chaotic. They grew extremely densely, with nodes stacked one on top of the other. The leaves were crinkled with intervein chlorosis and patchy pigmentation. These signs are similar to a viral infection, yet the seedlings were mostly able to resolve these issues with time. The crinkled yellowish leaves started looking more normal just as the seedlings began growing well and vining out. Even the runty seedlings that started nearly albino later recovered and starting producing chlorophyll. Some unusual characteristics that persist are leathery bronze-ish leaves, altered leaf venation, and flower sepal changes.

A photo showing the lack of internode space and malformed leaves of the initial growth:

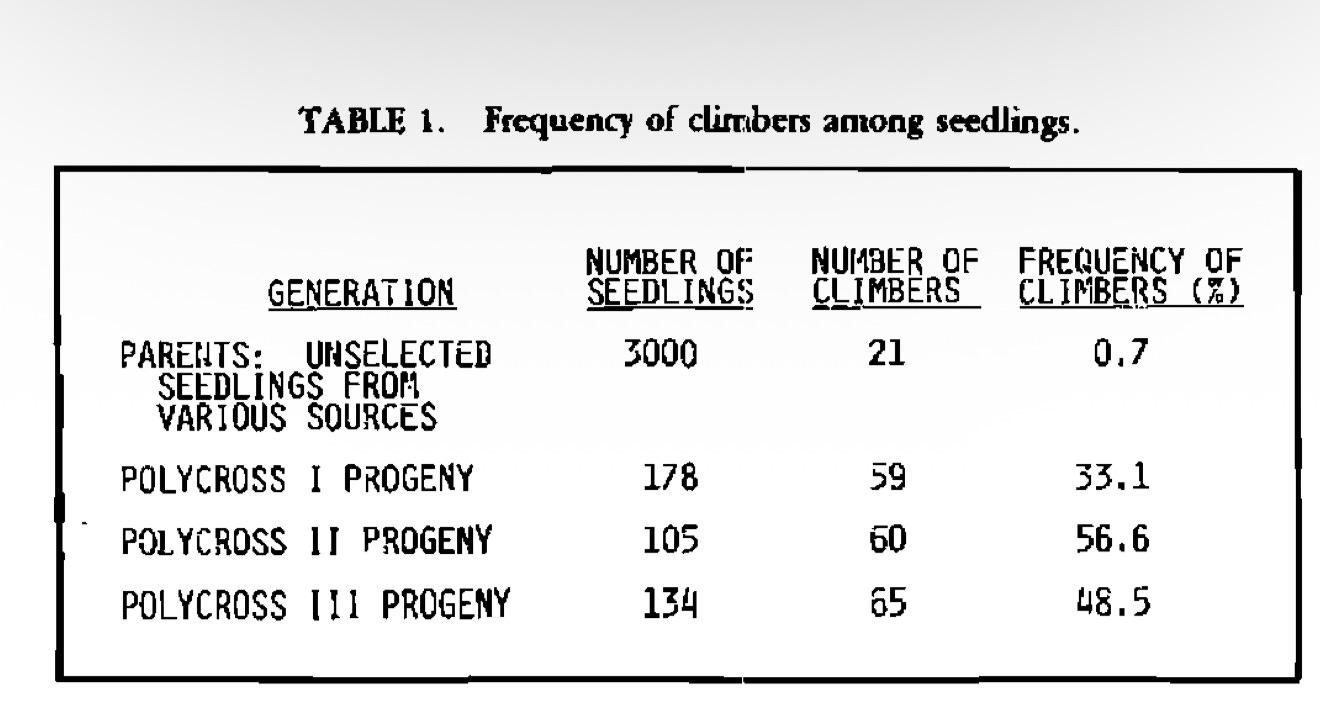

As the seedlings stabilized some, their twining nature was revealed. The seed parent did have the primitive, less-domesticated phenotype (thin twining pubescent vines) but was clearly the odd one out among its siblings in this regard. But just how uncommon is the climbing trait in sweet potato seedlings? Having grown out only ~30 seedlings this year, I couldn’t conclude much. Several sweet potato studies mention the climbing trait, usually in a list of traits to be selected against. There is a single paper on breeding sweet potatoes for the vining trait. In St. Croix in the early 80s, the Caribbean Food Crops Society wanted to produce vining sweet potatoes to compete better against weeds and climb up support plants like corn in polycultures (source). This breeding project was directed specifically at small farms with diverse crops. The paper gives data for the rate of occurrence of the climbing habit. In a group of 3000 seedlings from diverse sources, only 21 were climbing. After two additional rounds of poly-crossing the climbers, the trait increased to around 50%. However, many of the climbers resulting from the poly-crosses had a virus like syndrome and didn’t thrive. It’s an interesting paper that’s worth taking a look at.

In the case of these distant hybrid seedlings, all of them so far are climbers, a highly unusual distribution for that trait. Such a skewed distribution appears to be a result of hybridizing a vining sweet potato with a vining wild relative. This also reduces the chromosome number from hexaploid down to tetraploid (in theory). The entire tapestry of evidence so far, from the genome shock to novel traits like leathery leaves with unusual venation, makes a compelling case for distant hybridization. Besides being all vining, many other traits vary dramatically among the seedlings such as leaf texture, leaf size, leaf shape, stem thickness, and pubescence.

The below photo shows stress from genome shock (malformed, yellowish leaves with exudates on the veins) as well novel traits (leathery leaves with altered venation):

Another interesting feature of the hybrid seedlings is the sepals, which are a key identifying feature for Ipomoea species. In these seedlings, the sepals are long and tapered compared to I. batatas. Also, the calyces are loose and star-like instead of cupping the bud tightly like batatas. These features are both consistent with I. pandurata influence.

I. batatas sepals are 6-12mm in length, often on the lower end, whereas the seedling in the above photo has sepals about 14-16mm. Another identifying feature is the outer sepal to inner sepal size ratio of a calyx. In sweet potato, outer sepals are shorter than the inner sepals, with respective lengths of about ~7mm / 11mm. Pandurata on the other hand has close to an equal ratio of outer to inner sepals, with lengths of ~15mm / 16mm (source).

The next update on these seedlings will probably be the end of January. Hopefully the impressive combining ability bodes well for fertility and future intercrossing. One powerful thing that this experiment shows is that wide crossing barriers can be selected against. Regardless of whether the selection is developmental (first flowering) or genetic (intrinsically more permissive flowers), with the right conditions sweet potato distant hybridization is able to easily go much further what has been reported. Tricks such as plant hormones aren’t necessarily required to generate a hybrid population. Other vegetatively propagated crop species may also be able to relax their crossing barriers by similar methods.

Thanks for the update! Makes me wonder if crosses with something like the super cold hard field bindweed (convolvulus sp) could work. Hard to find info on their genetics

Love the update!